Workshop Steps

- 0 - About Programming

- 1 - Setting Up

- 2 - Values and operations

- 3 - Variables

- 4 - Conditions

- 5 - Array

- 6 - Objects

- 7 - Functions

- 8 - Functions and Objects

- 9 - Loops

- 10 - External Scripts

- 11 - The DOM

- 12 - And now what?

Useful Links

Step 7 - Functions

Functions are a way of taking the big todo list of our program and breaking it up into a series of smaller ones. It’s a little bit like writing lots of little program inside of your program (we heard you like programs so we put programs in your program).

We’ve been using functions so far to assign behaviour to events, specifically the onclick events of our buttons, but that isn’t the only place you can use functions.

Breaking your code up into functions is helpful because it lets us write our big programs as though they were a bunch of little ones instead.

- Small programs are easier to write than big ones.

- It can make our programs easier to read and understand.

- It can also save you time by letting you reuse your functions in multiple places.

So lets explore functions by creating a new app that lets us explore functions some more.

Specifically the things we are going to investigate about functions are:

- declaring,

- invoking,

- parameters and arguments,

- return values

Create our HTML

Create a new file with the following HTML.

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<meta charset="utf-8">

<title>Learning JS workshop</title>

</head>

<body>

<div style="padding:10px; margin: 15px; border:1px solid grey; background-color:#ffffff">

Background: <input id="bgColorInput" name="background" type="color" value="#ffffff" />

Row1: <input id="row1ColorInput" name="row1" type="color" value="#ffffff" />

Row2: <input id="row2ColorInput" name="row2" type="color" value="#ffffff" />

</div>

<div id="message"></div>

<div id="row1" style="width:100%;height:100px"></div>

<div id="row2" style="width:100%;height:100px"></div>

</body>

<script>

</script>

</html>

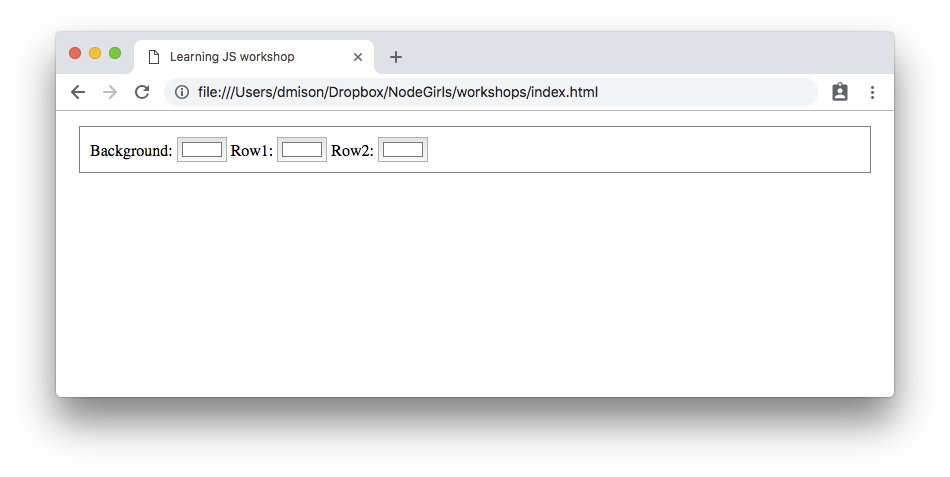

Save it and check it out in your browser.

You should see three colour selection elements that when clicked open colour pickers.

This is done by using <input> elements with type set to color.

There are also three <div>s with no content.

Notice how each <input> has a name attribute, two of which correspond to the ids of the empty <div>s and the other name is just 'background'? We’ll use that information later so that when one of the <input>s changes colour we know the right thing to update.

What we are going to do is add javascript code in our <script> tag so that selecting colours will cause the background colour of the page or the divs to update to match.

Declaring Functions

Creating a new function is often called declaring it.

Let’s declare a new function called handleColorChange:

function handleColorChange(event){

}

Declaring a function requires four things:

- The

functionkeyword. - The name for the new function,

handleColorChange. - The optional parameter list in a pair of parentheses,

(event) - The body of the function surrounded by opening and closing braces,

{}

handleColorChange doesn’t do anything yet, but let’s assign it to the onchange event of each of our colour inputs.

document.getElementById('bgColorInput').onchange = handleColorChange;

document.getElementById('row1ColorInput').onchange = handleColorChange;

document.getElementById('row2ColorInput').onchange = handleColorChange;

Parameters and Arguments

Arguments are a way of sending values into a function from the code that invokes it. This is usually called passing arguments.

Parameters are how you map those values into variables that you use in your function.

In the declaration of handleColorChange we defined one parameter, called event.

Functions that are attached to events are invoked by the browser when the event happens. When this happens the browser will always pass an argument to the function. This argument contains all the data about the event. This happens behind the scenes.

So what’s in event? Let’s put a temporary console.log statement into handleColorChange to find out.

Update handleColorChange like this:

function handleColorChange(event){

console.log(event);

}

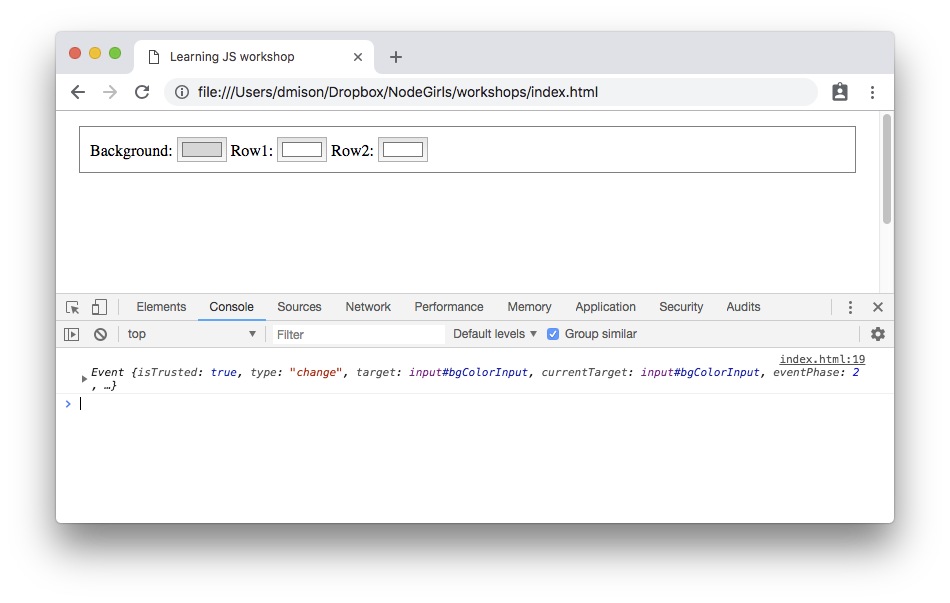

Refresh the page, open the console and click on one of the colour inputs and try to change the colour.

The console will display something like this:

This is our event data. You should be able to click the little triangle and expand it to see all the details.

The event object contains a lot of properties with details about the event, but the interesting thing for us is the target property.

target is another object which represents the element which was the source of the event.

It is from this that we can find out what the new colour selection is, and anything else we want to know.

So lets do that, lets change that log statement to show instead just the details we are interested in.

function handleColorChange(event){

console.log(event.target.name, event.target.value);

}

Ok so now handleColorChange has the the information it needs: the input name and the new colour code. But we aren’t going to update the colours here, we are going to create a new function to do that, and invoke it from here instead.

So let’s quickly declare that function with an empty body:

function setColor(color, element){

}

Notice how it has two parameters, color and element ?

Ok so how do we invoke it from handleColorChange?

Invoking Functions

Invoking a function is easy, you just put the name of the function followed by parentheses. If you want to pass arguments to the function you put those inside the parentheses.

So lets update handleColorChange so it invokes setColor, and setColor so it just logs it’s parameters.

function setColor(color, elementId){

console.log(color, elementId);

}

function handleColorChange(event){

setColor(event.target.value, event.target.name);

}

See how we are passing values from one function to the next.

Anyway, still not really useful. Let’s have handleColorChange make some decisions:

function colorChange(event){

if(event.target.name === 'background'){

setColor(event.target.value);

} else {

setColor(event.target.value, event.target.name);

}

}

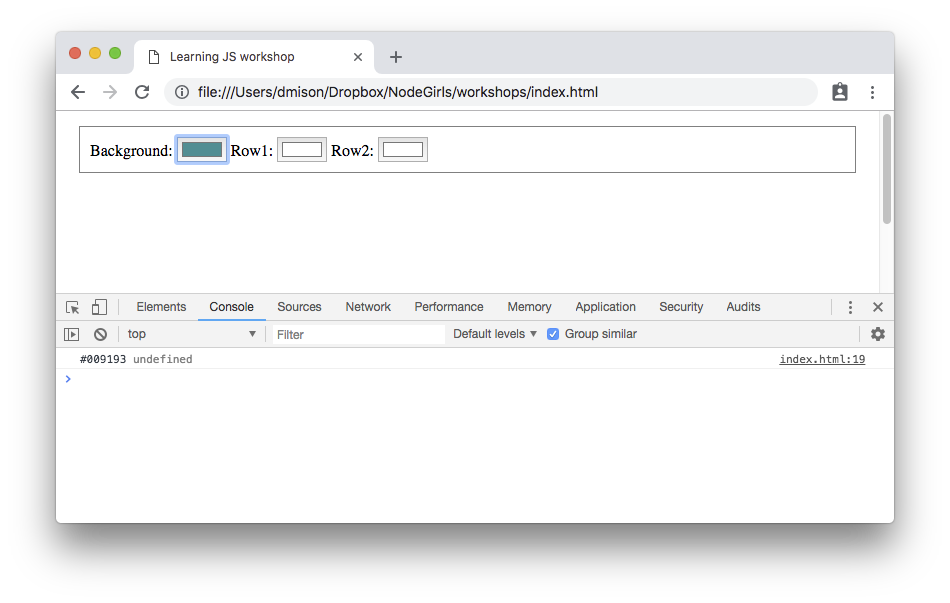

So now if when you try to change the background colour, setColor only gets invoked with one parameter. So what happens to the second one?

Try it out & check the log to see.

If fewer arguments are passed than parameters are declared, then the remaining parameters contain the special value undefined, just like uninitialised variables.

And we are going to take advantage of this in setColor because setting the page colour is going to be a little different to the div colours.

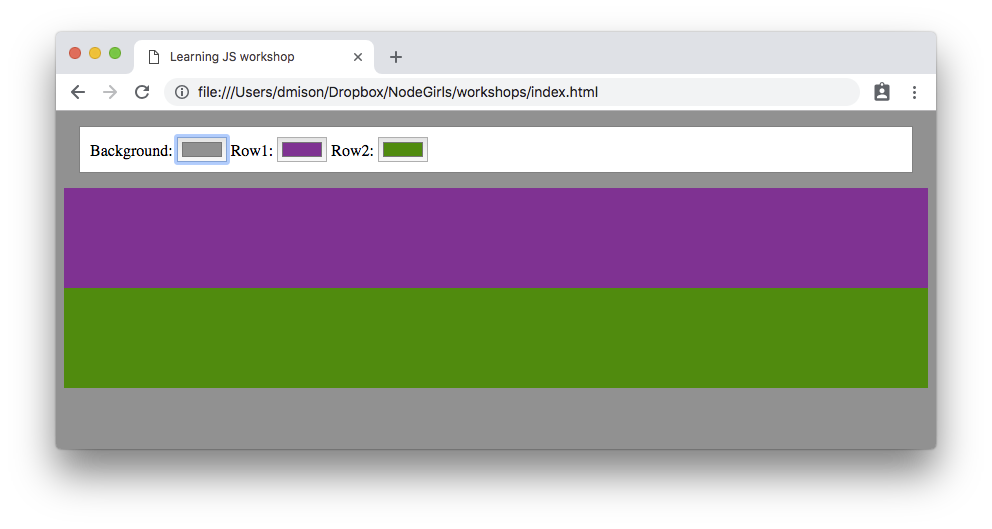

Let’s update setColor:

function setColor(color, elementId){

if(elementId === undefined){

document.bgColor = color;

} else {

document.getElementById(elementId).style.backgroundColor = color;

}

}

So now if elementId is undefined it means update the background colour with the value of color. Otherwise get the element with the passed id and set its background colour.

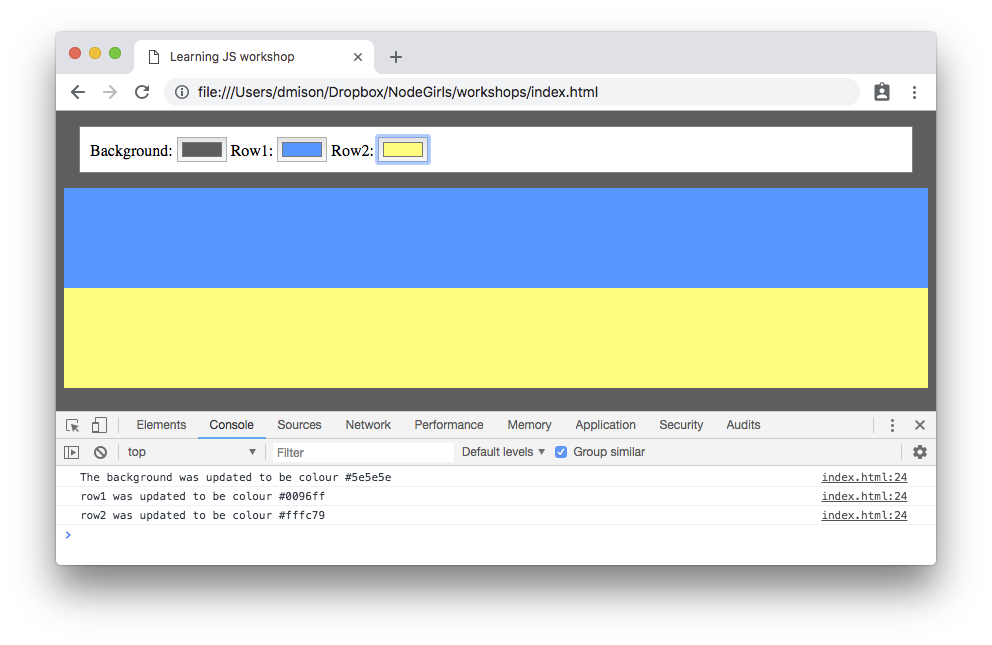

Check it out in your browser.

Return Values

Functions have one more feature we haven’t explicitly used yet, return values.

Return values are a way that functions can send data back to the code that invoked it. Return values are sometimes called a function’s result.

This is done in the function with the return keyword and a value.

To see this in action, lets make a function that we pass our elementId & color to and it returns a string describing the change:

function getMessage(color, elementId){

if(elementId === undefined){

return 'The background was updated to be colour '+color;

}

return elementId + ' was updated to be colour '+color;

}

When the function encounters the return keyword, the function stops running immediately and control passes back to the code that invoked it with the value.

Now let’s invoke it from setColor and just log the result. Add this line to the end of setColor:

console.log(getMessage(color, elementId));

Save it and test it in the browser. See how the return value from getMessage is “passed back” to console.log

The returned value is substituted in the place of the function call just like a resolved expression.

Let’s do something more interesting with it now. Replace the console.log line with the following:

document.getElementById('message').innerText = getMessage(color, elementId);

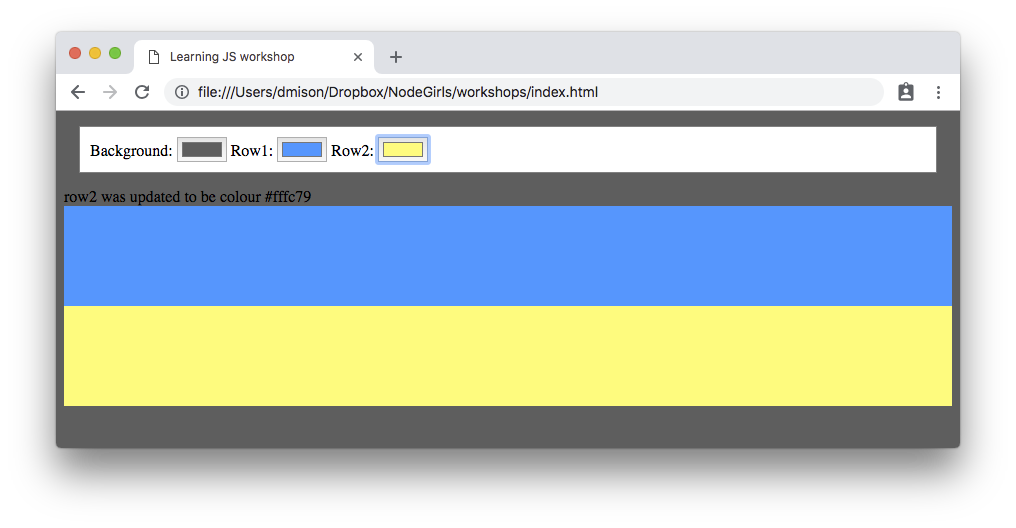

Now when you change colours the appropriate message should be displayed.

You could move that line to handleColorChange instead of it being in setColor, but you would have to make a few small changes.

What do you think those changes would have to be? Give it a try.

Muses Code

Muses Code